VIDEO AND PHOTO GALLERY ABOVE

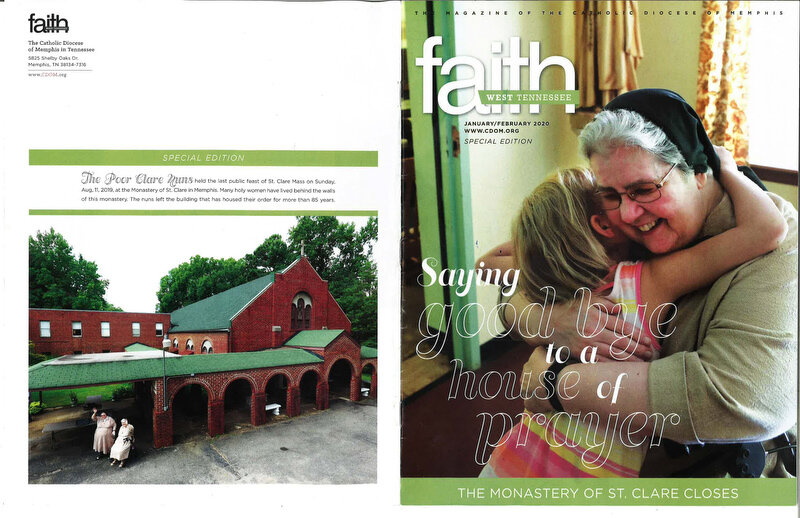

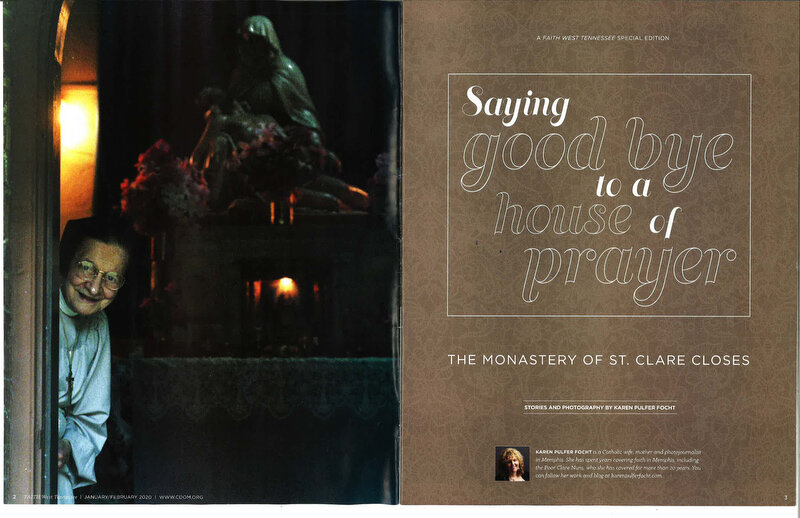

Below is a photo gallery of the January 2020 West Tennessee Faith Special Edition published by the Catholic Diocese of Memphis (Photographed and written by Karen Pulfer Focht ©) UPDATE: Karen was awarded a First place award from the Catholic Press Association for both Writing and Photography of this story in June of 2021.

You may make prayer requests to the Poor Clares by email at prayer@poorclaresc.com

POOR CLARE NUNS LEAVE MEMPHIS

Written by: Karen Pulfer Focht © All Rights Reserved

Memphis, Tennessee - As Christmas approached and 2019 came to a close, one of the last Catholic contemplative monastery in Tennessee quietly closed.

An 88- year-old priest, Father David Knight, was the last remaining resident. He had hoped to live out his days in his tiny single room with a connecting office where he has written over 40 books.

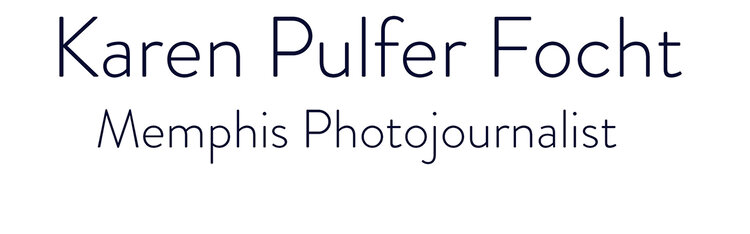

Concealed behind tall brick walls and strong iron gates in a struggling Memphis neighborhood, a group of nuns has been quietly praying for the city and its people since 1932.

Few people have been behind these walls of the Monastery of St. Clare. The silent and prayerful lives of the women, who have chosen to live here in community, has remained a mystery and a curiosity to most outsiders.

But a loyal group of friends and followers have supported them in every way you can imagine, only asking for prayer in return.

In a neighborhood that is plagued by crime and residents fighting to climb out of poverty, these women have chosen a life that St. Clare called the “privilege of highest poverty.” The nuns rely on these friends for generosity, food, donations and even occasional help around the monastery.

They have been called to a life of prayer and silence; to live in community and in radical poverty. They have chosen to live by the Rule of St. Clare (1194-1253), a set of guidelines of poverty and piety, based on how she lived during the middle ages in Assisi, Italy. She was the first woman to write a set of guidelines for a religious community. It was a bold gesture, since all religious group rules in her day were determined by men.

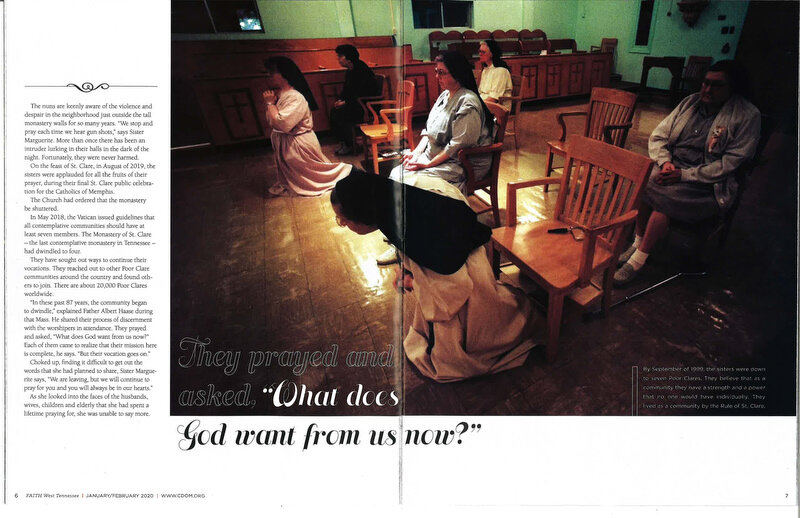

The nuns are keenly aware of the violence and despair in the neighborhood just outside the tall monastery walls for so many years. “We stop and pray each time we hear gun shots,” says Sister Marguerite. More than once there has been an intruder lurking in their halls in the dark of the night. Fortunately, they were never harmed.

On the Feast of St. Clare, in August of 2019, the sisters were applauded for all the fruits of their prayer, during their final St. Clare public celebration for the Catholics of Memphis.

The church had ordered that the monastery be shuttered.

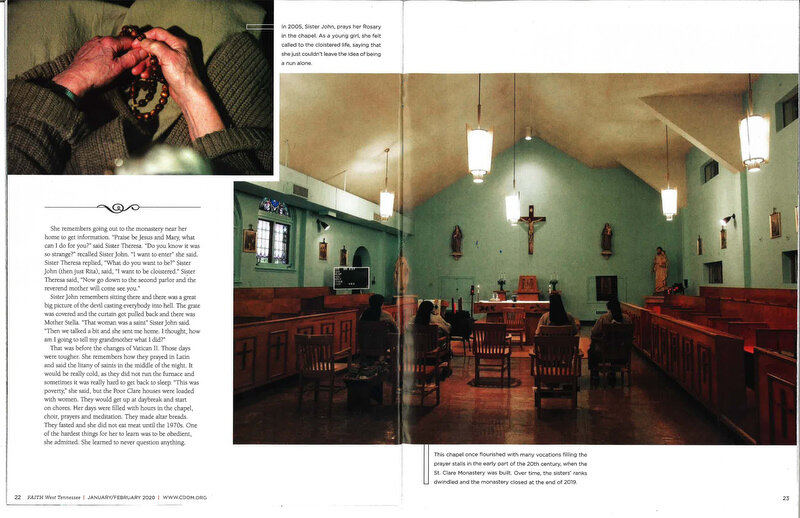

In May 2018 the Vatican issued guidelines that all contemplative communities should have at least seven members. The Monastery of St. Clare had dwindled to four.

They have sought out ways to continue their vocations. They reached out to other Poor Clare communities around the country and found others to join. There are about 20,000 Poor Clares worldwide.

“In these past 87 years, the community began to dwindle,” explained Father Albert Haase during that Mass. He shared their process of discernment with the worshipers in attendance. They prayed and asked “what does God want from us now?” Each of them came to realize, their mission here is complete, he says. “But their vocation goes on.”

Choked up, finding it difficult to get out the words that she had planned to share, Sr. Marguerite said, “We are leaving, but we will continue to pray for you and you will always be in our hearts.”

As she looked into the faces of the husbands, wives, children and elderly that she had spent a lifetime praying for, she was unable to say more.

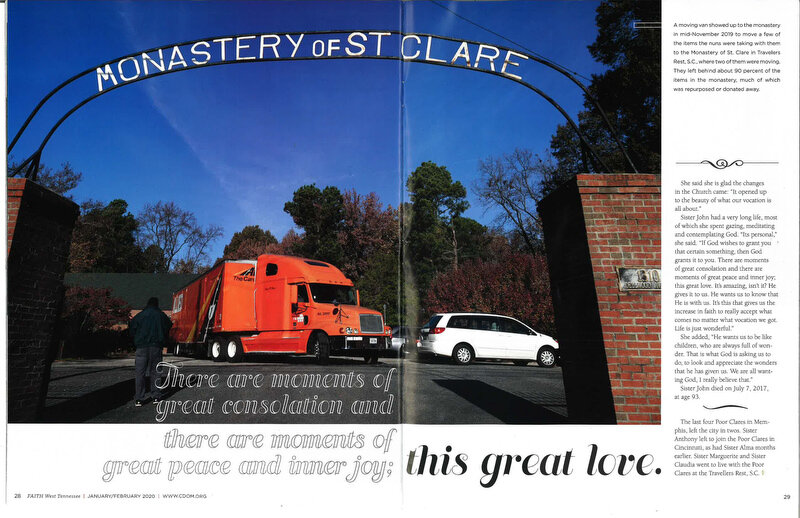

So for the last several months, they have been packing up the monastery. A sewing room filled with shelves of brown and black material for veils and habits were cleared out. Cabinets filled with candles and other materials used in the liturgy were cleaned and given away. Statues of saints were taken down from their pedestals. Many of the items will be used in other churches in the region.

Other sisters came in small numbers from their respective new communities, to help the aging four Memphis sisters with the daunting task of unraveling more than 85 years of religious life in a monastery that was originally built for many more. At its peak, the monastery housed 30 holy women.

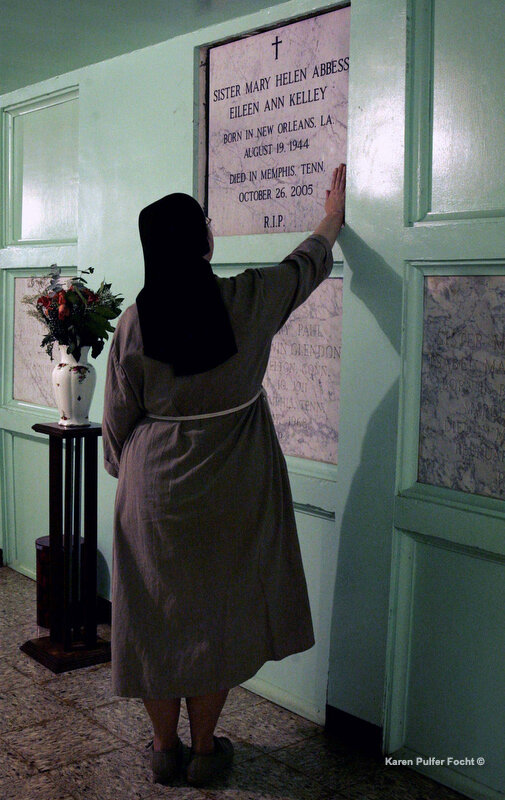

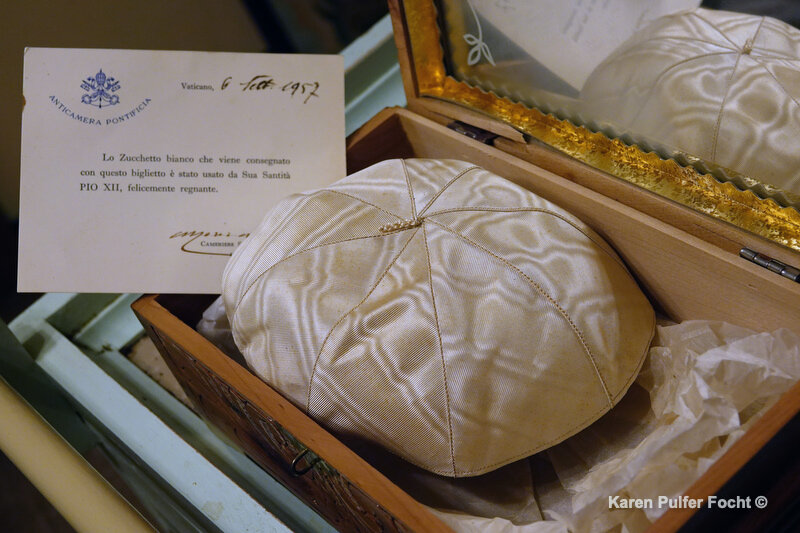

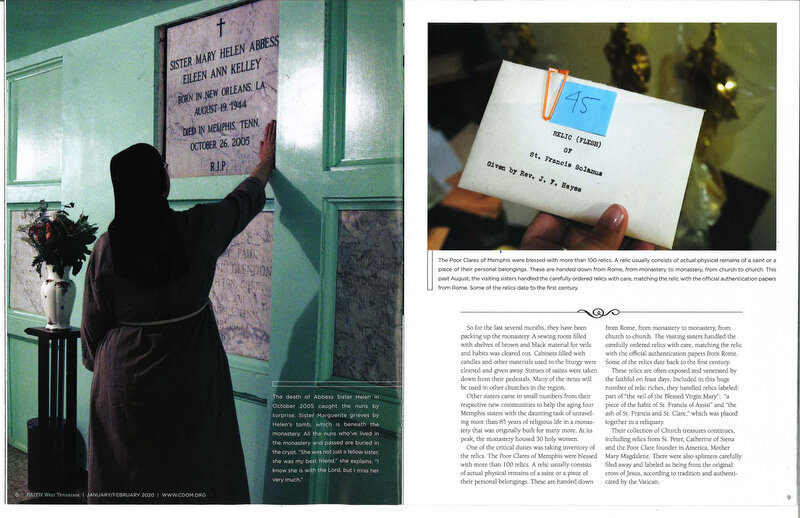

One of the critical duties was taking inventory of the relics. The Poor Clares of Memphis were blessed with over 100 relics. A relic usually consists of actual physical remains of a saint or a piece of their personal belongings. These are handed down from Rome, from monastery to monastery, from church to church. The visiting sisters handled the carefully-ordered relics with care, matching the relic with the official authentication papers from Rome. Some of the relics go back the first century.

These relics are often exposed and venerated by the faithful on feast days. Included in this huge number of relic riches, they handled relics labeled: part of “the veil of the Blessed Virgin Mary; “ a piece of the habit of St. Francis of Assisi; the ash of St. Francis and St. Clare which was placed together in a reliquary.

Their collection of church treasures continues, including relics from St. Peter, Catherine of Sienna and the Poor Clare founder in America, Mother Mary Magdalene. There were also splinters carefully filed away, labeled as being from the original cross of Jesus, according to tradition and authenticated by the Vatican.

Bishop A. Smith brought many of the relics to the monastery from when he visited Rome. Smith invited the Poor Clares to Memphis in the early 1930s. He said when he became a bishop, he wanted the Poor Clares here to pray for the priests.

The relics will go to the diocese and other churches that express interest.

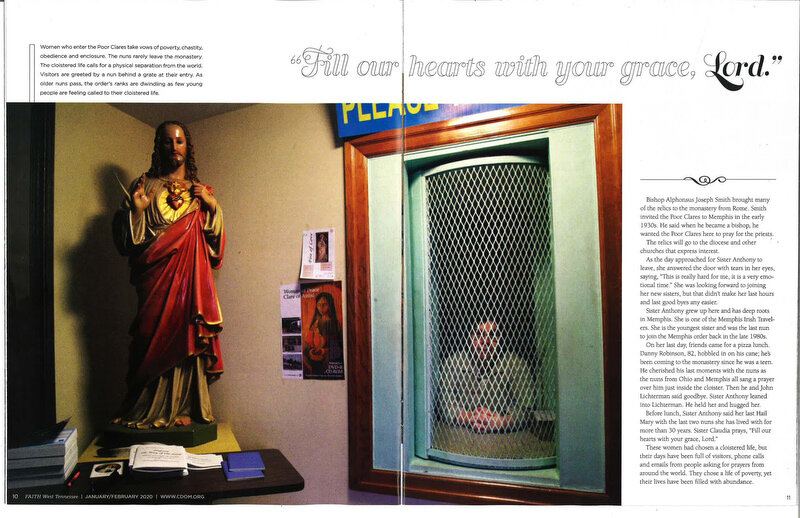

As the day approached for Sr. Anthony to leave, she answered the door with tears in her eyes saying “this is really hard for me, it is a very emotional time.” She was looking forward to joining her new sisters but that didn’t make her last hours and last goodbyes any easier.

Sr. Anthony grew up here and has deep roots in Memphis. She is one of the Memphis Irish Travelers. She is the youngest sister and was the last nun to join the Memphis order back in the late 80’s.

On her last day, friends came for a pizza lunch. Danny Robinson, 82, hobbled in on his cane; he’s been coming to the monastery since he was a teen. He cherished his last moments with the nuns as the nuns from Ohio and Memphis all sang a prayer over him just inside the cloister. Then he and John Lichterman said goodbye. Sr. Anthony leaned into Lichterman. He held her and hugged her.

Before lunch, Sister Anthony said her last Hail Mary with the last two nuns she has lived with for more than 30 years. Sister Claudia prays, “Fill our hearts with your grace, Lord.”

These women had chosen a cloistered life, but their days have been full of visitors, phone calls and emails from people asking for prayers from around the world. They chose a life of poverty, yet their lives have been filled with abundance.

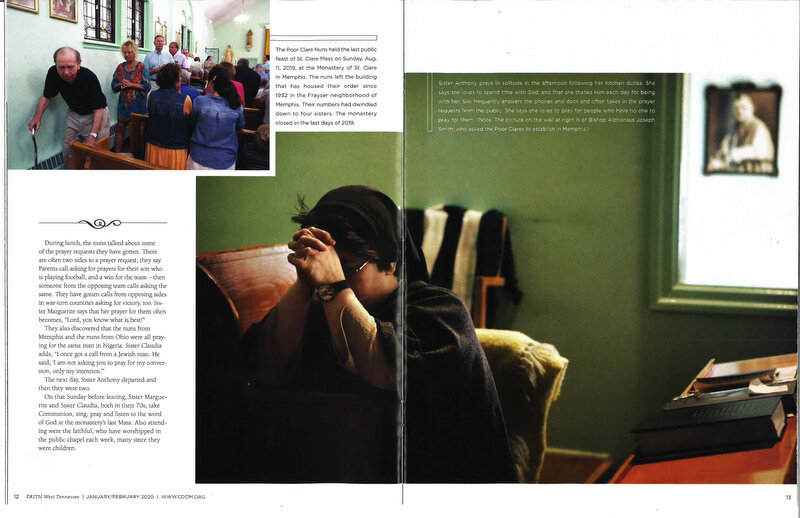

During lunch, the nuns talked about some of the prayer requests they have gotten. There are often two sides to a prayer request, they say. Parents call asking for prayers for their son who is playing football, and a win for the team--then someone from the opposing team calls asking the same. They have gotten calls from opposing sides in war-torn countries asking for victory too. Sister Marguerite says that her prayer for them often becomes, “Lord, you know what is best!”

They also discovered that the nuns from Memphis and the nuns from Ohio were all praying for the same man in Nigeria. Sr. Claudia adds, “I once got a call from a Jewish man. He said, I am not asking you to pray for my conversion, only my intention.”

The next day, Sr. Anthony departed and then they were two.

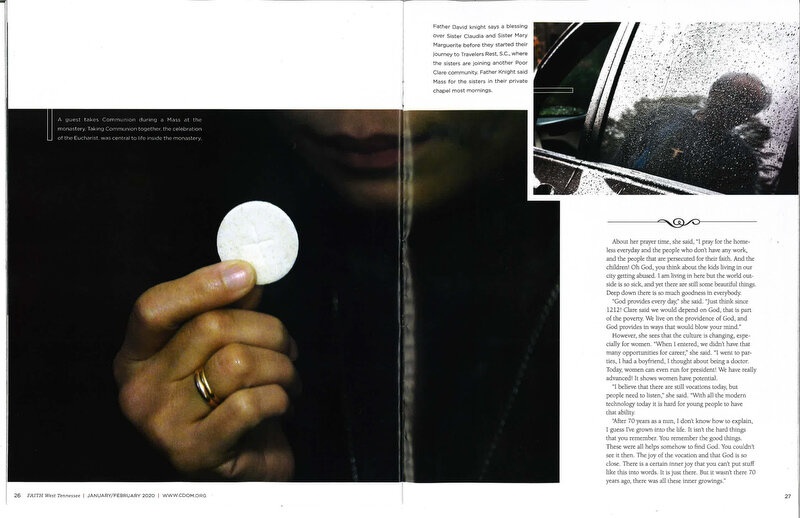

On that Sunday before leaving, Sr. Marguerite and Sr. Claudia, both in their 70’s, take communion, sing, pray and listen to the word of God at the monastery’s last Mass . Also attending were the faithful, who have worshipped in the public chapel each week, many since they were children.

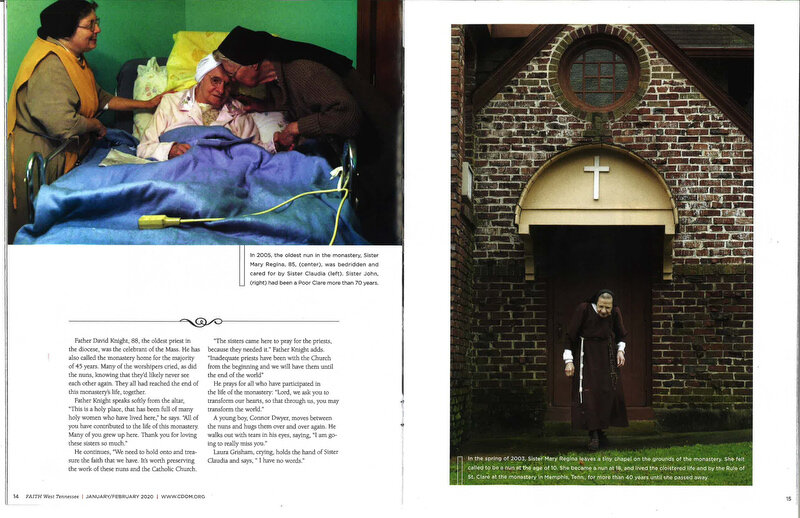

Father David Knight, 88, the oldest priest in the diocese, was the celebrant of the Mass. He has also called the monastery home for the majority of 45 years. Many of the worshippers cried, as did the nuns, knowing that they’d likely never see each other again. They all had reached the end of this monastery’s life, together.

Father Knight speaks softly from the altar, “This is a holy place, that has been full of many holy women who have lived here,” he said. “All of you have contributed to the life of this monastery. Many of you grew up here. Thank you for loving these sisters so much.”

He continues, “We need to hold onto and treasure the faith that we have. It’s worth preserving the work of these nuns and the Catholic Church.”

“The sisters came here to pray for the priests, because they needed it.” Father Knight adds. “Inadequate priests have been with the church from the beginning and we will have them until the end of the world”

He prays for all who have participated in the life of the monastery, “Lord, we ask you to transform our hearts, so that through us, you may transform the world.”

A young boy, Connor Dwyer, moves between the nuns and hugs the nuns over and over again. He walks out with tears in his eyes saying “I am going to really miss you.”

Laura Grisham, cries, holds the hand of Sister Claudia and says, “ I have no words.”

With just a few days left, the sisters packed their belongings and said goodbye to this endless stream of visitors.

This is the hardest part for Sr. Marguerite. People often tell the Poor Clares their most intimate secrets and problems. “A bond is very quickly established when you pray for people” she says.

She is a bit nervous about this major transition and about learning a new way. “We follow the same way of life, but each house expresses it in its unique way” she says. She says she decided to drive to South Carolina, instead of fly, because that will make her transition easier.

On the day Sr. Marguerite and Sr. Claudia leave, Father Knight has a tiny Mass at a table in the guest quarters. A handful of people are present. The nuns are in travel clothes instead of their habits. Their chapel has been emptied; the tabernacle has been removed.

Father Knight gives a brief homily, “Jesus is everywhere, you are going from a holy place to a holy place.”

“Everything is changing here, you are leaving this house, this town, these people, but you will still be leading a Poor Clare life,” Father Knight says, “This is a type of death but God is with us all the time he is with us where ever we go.” He reminds them, “Our happiness is not dependent on anything on this earth.”

“We have to keep on this journey where ever it leads us,” Sr. Claudia says.

Before they pull away on a rainy, gray November morning, Father Knight gives them one last blessing through the car window.

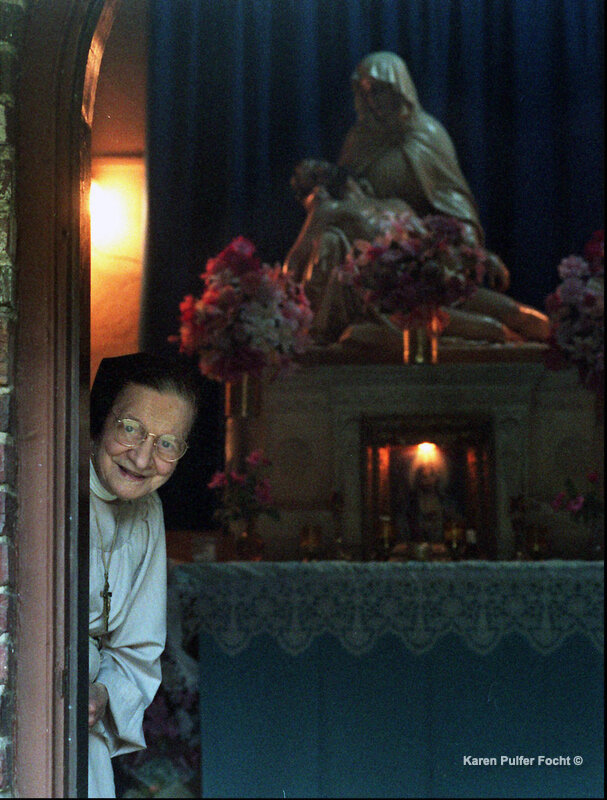

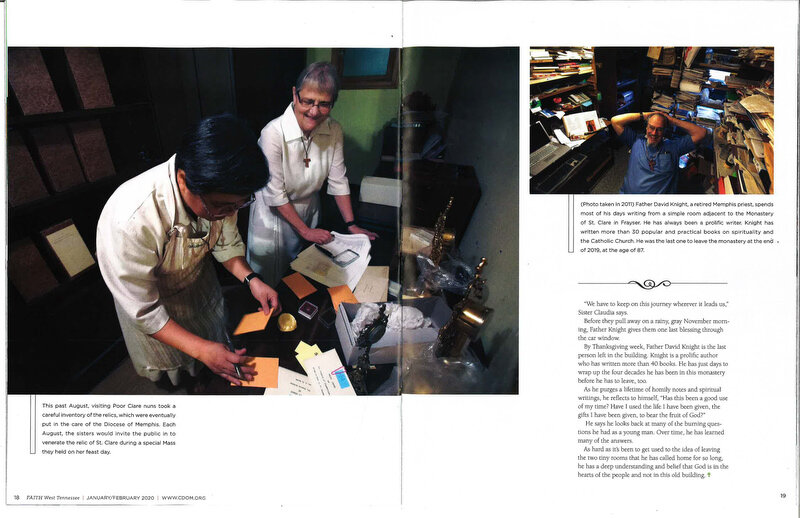

By Thanksgiving week, Father David Knight is the last person left in the building. Knight is a prolific author, who has written over 40 books. He has just days to wrap up the four decades he has been in this monastery before he has to leave too.

As he purges a lifetime of homily notes and spiritual writings, he reflects to himself, “has this been a good use of my time?” “Have I used the life I have been given, the gifts I have been given, to bear the fruit of God?”

He says he looks back at many of the burning questions he had a young man. Over time he has learned many of the answers.

As hard as it’s been to get used to the idea of leaving the two tiny rooms that he has called home for so long, he as a deep understanding and belief that God is in the hearts of the people and not in this old building.

NOTE At the end* the last four Poor Clare’s in Memphis, left the city in twos. Sister Anthony left to join the Poor Clare’s in Cincinnati, as did Sister Alma months earlier. Sister Marguerite and Sister Claudia went to live with the Poor Clare’s at the Travellers Rest, South Carolina.

Karen Pulfer Focht is an independent photojournalist in Memphis, Tennessee. She has covered faith in Memphis and the Poor Clare nuns for over 20 years.

www.karenpulferfocht.com

A POOR CLARE LIFE

Written by Karen Pulfer Focht ©

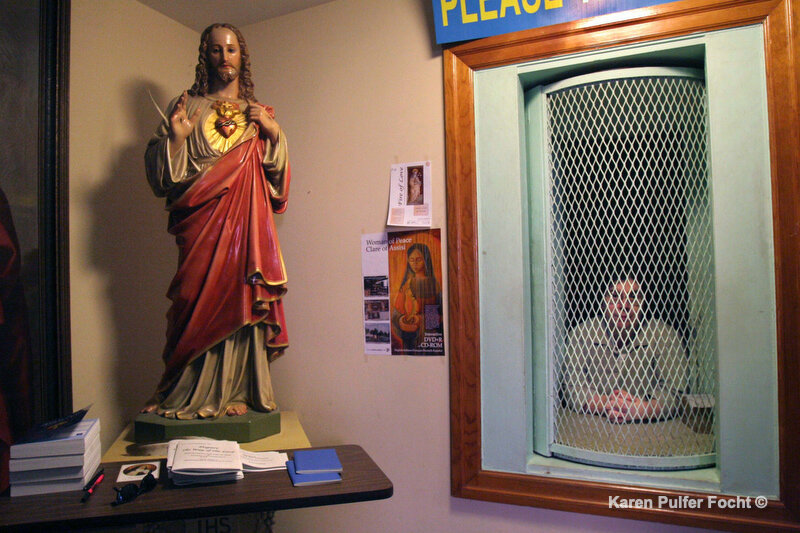

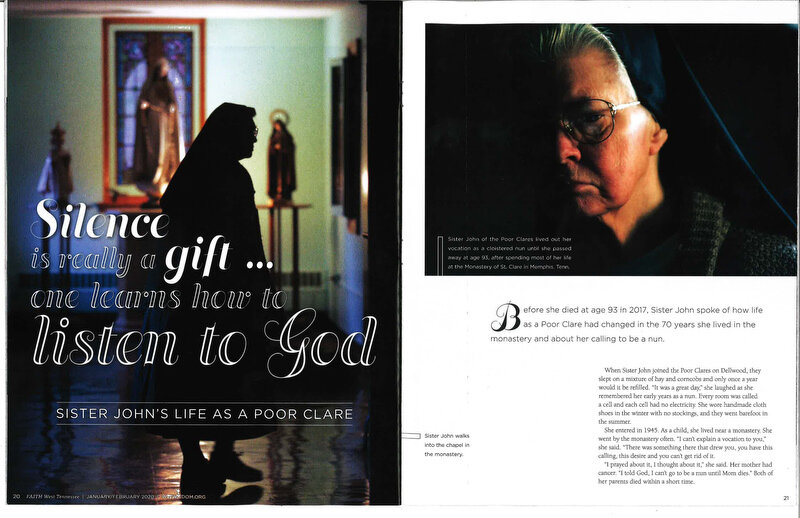

Memphis, Tennessee- Before she died at age 93 in 2017, Sister John spoke of how life as a Poor Clare had changed in the 70 years she lived in the monastery and about her calling to be a nun. ~Karen Pulfer Focht

When Sister John joined the Poor Clares on Dellwood, they slept on a mixture of hay and corncobs and only once a year would it be refilled. “It was a great day,” she laughed as she remembered her early years as a nun. Every room was called a cell and each cell had no electricity. She wore hand made cloth shoes in the winter with no stockings and they went barefoot in the summer.

She entered in 1945. As a child she lived near a monastery. She went by the monastery often. “I can’t explain a vocation to you” she ponders her choice “there was something there that drew you, you have this calling, this desire and you can’t get rid of it.”

“I prayed about it, I thought about it,” she said. Her mother had cancer. “I told God, I can’t go to be a nun until Mom dies.” Both of her parents died within a short time. She remembers going out to the monastery near her home to get information. “Praise be Jesus and Mary, what can I do for you?” said Sister Theresa. “Do you know it was so strange?” recalls sister John. “I want to enter” she said and Sister Theresa said, “What do you want to be?” to Sister John, who was then Rita, “I want to be cloistered.” Sister Theresa said, “now go down to the second parlor and the reverend mother will come see you.”

Sister John remembers sitting there and there was a great big picture of the devil casting everybody into hell. The grate was covered and the curtain got pulled back and there was Mother Stella. “That woman was a saint” Sister John said. “Then we talked a bit and she sent me home.” She said, “I thought, how am I going to tell my grandmother what I did?”

That was before Vatican II changes. Those days were tougher. She remembers how they prayed in Latin and said the litany of saints in the middle of the night. It would be really cold, as they did not run the furnace and sometimes it was really hard to get back to sleep. “This was poverty,” she said, but the Poor Clare houses were loaded with women.

They would get up at daybreak and start on chores. Her days were filled with hours in the chapel, choir, prayers and meditation. They made altar breads. They fasted and she did not eat meat until the 1970’s.

One of the hardest things for her to learn was to be obedient, she admitted. She learned to never question anything. Her days were spent in complete silence. She speaks softly as she conveys the teaching “the point is that the silence brings about that stillness, silence is really a gift that one learns how to listen to God. You may not get it for years and years. It is an effort that one has to make to really communicate with Jesus. It’s that relationship that the contemplative is called to.” She goes on with a joyful bliss in her voice, “it’s a process of inner purification.” She went on to explain how the Rule of St. Clare urges one to seek God.

“As a poor Clare to grow in God you have to become a person that is open to the sufferings and concerns of the people out there. Life goes on, if you are going to be helpful to the church, now you are to pray for the church and the world. That is the mission of the Poor Clares. If you don’t have a vocation to this life, you’d be miserable.” “We laugh about the old days and that. They were good, I don’t regret it, they were precious, and they had their own jewels. I lived with some very holy nuns. It’s a wonderful vocation,” she said.

About her prayer time, she says, “I pray for the homeless everyday and the people who don’t have any work, and the people that are persecuted for their faith. And the children! Oh God, you think about the kids living in our city getting abused. I am living in here but the world outside is so sick, and yet there are still some beautiful things. Deep down there is so much goodness in everybody.” “God provides every day.” She says, “Just think since 1212! Clare said, we would depend on God, that is part of the poverty. We live on the providence of God and God provides in ways that would blow your mind.”

However she sees that the culture is changing, especially for women. “When I entered we didn’t have that many opportunities for career” she said “I went to parties, I had a boyfriend, I thought about being a doctor. Today, women can even run for president! We have really advanced! It shows women have potential.”

“I believe that there are still vocations today but people need to listen.” She says, “With all the modern technology today it is hard for young people to have that ability.” When she thinks about the challenges that she has faced living a cloistered life “After 70 years as a nun, I don’t know how to explain, I guess I’ve grown into the life. It isn’t the hard things that you remember. You remember the good things. These were all helps somehow to find God. You couldn’t see it then. The joy of the vocation and that God is so close. There is a certain inner joy that you can’t put stuff like this into words. It is just there.

But it wasn’t there 70 years ago, there was all these inner- growings.” She said she is glad the changes in the church came. “It opened up to the beauty of what our vocation is all about.” Sr. John had a very long life most of which she spent gazing, meditating and contemplating God. “Its personal” she says reflecting, “If God wishes to grant you that certain something, than God grants it to you. There are moments of great consolation and there are moments of great peace and inner joy; this great love. It’s amazing isn’t it? He gives it to us. He wants us to know that he is with us. It’s this that gives us the increase in faith to really accept what comes no matter what vocation we got.

Life is just wonderful.” She says, “He wants us to be like children, who are always full of wonder. That is what God is asking us to do, to look and appreciate the wonders that he has given us. We are all wanting God, I really believe that.” ~~~~

Sr. John died July 7 th , 2017 at age 93.

Vatican issues new rules for communities of contemplative nuns

http://thedialog.org/vatican-news/vatican-issues-new-rules-for-communities-of-contemplative-nuns/